Alanis Obomsawin, visual artist, by Caroline Montpetit – Le Devoir

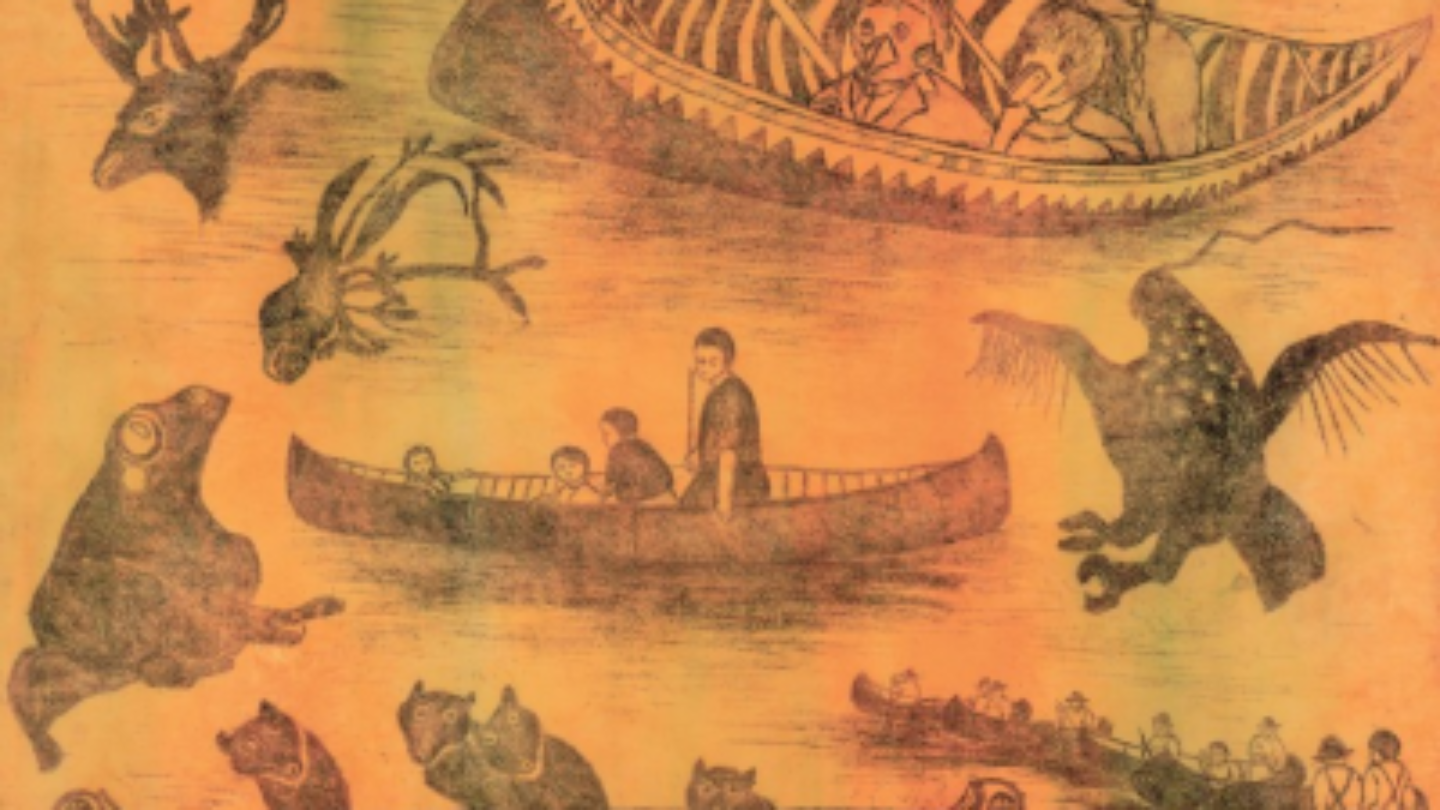

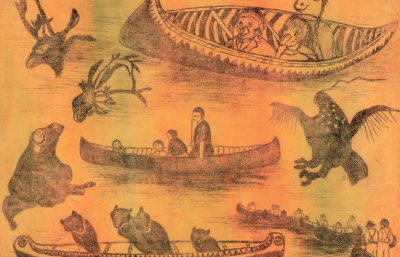

Illustration: Alanis Obomsawin Alanis Obomsawin, “The Great Visit”, 2007

Caroline Montpetit, Le Devoir, June 8, 2019 – After the 1990 Oka crisis, Wabanaki artist Alanis Obomsawin, known mainly as a documentary filmmaker, felt the need to express herself through the visual arts. She then created a monotype on plexiglass representing a horse’s head and called it Cheval vert. This green horse, she’s already met him in a dream. In this dream, the horse chased her every day. One day, to avoid it, she enters a house where a man sleeps, which she must not wake up otherwise she will be raped. She comes into contact with the horse and promises to visit him every day in exchange for his freedom.

At the age of 86, Alanis Obomsawin presented her first solo exhibition of her work, mainly drypoint prints, at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts. The works presented were all made after 1990, although the artist began working on engraving in the 1970s. There are themes dear to the artist’s heart, several engravings related to the animal world, Amerindian history and motherhood. A series of engravings, showing mothers with their children, is entitled Mother of So Many Children. That is the name Alanis Obomsawin gave to a film she made in 1975. “It was the Year of the Woman,” he recalls. God, that was hard to achieve. Today, it’s easier, I don’t need to fight anymore,” she says in an interview. In general, she is very optimistic about the situation of Aboriginal people in Canada. She is happy to see Aboriginal youth getting up and fighting rather than thinking about suicide. Nevertheless, his work reflects some of the misery endured by indigenous communities, and Wabanaki in particular, over the decades.

“In Aboriginal culture, women kept children with them at all times. They wore them to work until they were four or five years old. It was a very important aspect of culture,” she says. However, one of his engravings, entitled Qu’est devenu mon enfant, illustrates the drama experienced by mothers whose children were forced to be taken to residential school. Some of these mothers never saw their children again, and never knew what had happened to them.

Braided baskets The exhibition also presents elements of Wabanaki culture, including the fabulous baskets that have made the reputation of its people. “At one time,” says Alanis Obomsawin, “everyone made baskets. “She says she misses the sweetgrass that dried in front of every house in Odanak. One of his works is dedicated to Agnès Panadis, a basket weaver known in the village. The museum room dedicated to the exhibition also offers magnificent specimens of these baskets. A wedding basket, designed by Emilia M’Sadoqies, is decorated with a multitude of small baskets, and a bird carrying one in its beak. And you have to hear Alanis Obomsawin talk about how her mother ran away to avoid selling the baskets to tourists. The exhibition also features an embroidered collar and bag from Alanis Obomsawin’s grandmother, Marie-Anne Nagajoie. “My grandmother, Marie-Anne Nagajoie, said, “Mariah will have a difficult life because she refuses to make baskets,” she says.

Another engraving refers to Ozonkhiline, the Waban-Aki who walked the rails from Odanak to Dartmouth College in New Hampshire in 1823. “It was a time when we were losing all the land,” she says. Dartmouth University was built on Aboriginal land. For this reason, Aboriginal people had the right to attend classes free of charge. “It was education that Ozonkhilin had gone to look for on foot. Upon his return to the village, Ozonkhilin became a Methodist pastor and introduced Protestantism to the village.

The importance of dreams Dreams, very important in Native American culture, have always been of great help to Alanis Obomsawin, who found peace in sleep. She remembers that in one of them, foreigners living in Odanak wanted to bury her alive because she was different. In her dream, she emerged from the cemetery, topped with animal woods. From that moment on, she was able to move around the village comfortably because she had become invisible.

Yet Alanis Obomsawin is anything but invisible or buried. On Friday, she gave interviews dressed in red, in honour of murdered or missing Aboriginal women and girls. This is the colour that the museum gave to the walls of the exhibition, for the same reason.

Alanis Obomsawin, engraved works. An artist and her nation: the waban-akis basket makers of Odanak Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, June 7 to August 25, 2019